Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (September 129 AD – c. 200/c. 216), often Anglicized as Galen and better known as Galen of Pergamon was a prominent Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire.

Arguably the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology, and neurology, as well as philosophy and logic.

The son of Aelius Nicon, a wealthy architect with scholarly interests, Galen received a comprehensive education that prepared him for a successful career as a physician and philosopher.

Born in Pergamon, Galen traveled extensively, exposing himself to a wide variety of medical theories and discoveries before settling in Rome.

Where he served prominent members of Roman society and eventually was given the position of personal physician to several emperors.

Galen's understanding of anatomy and medicine was principally influenced by the then-current theory of humorism, as advanced by ancient Greek physicians such as Hippocrates.

His theories dominated and influenced Western medical science for more than 1,300 years.

His anatomical reports, based mainly on dissection of monkeys, especially the Barbary macaque, and pigs, remained uncontested until 1543.

Galen's theory of the physiology of the circulatory system endured until 1628, when William Harvey published his treatise entitled De motu cordis, in which he established that blood circulates, with the heart acting as a pump.

Galen saw himself as both a physician and a philosopher, as he wrote in his treatise entitled that the Best Physician is Also a Philosopher.

In medieval Europe, Galen's writings on anatomy became the mainstay of the medieval physician's university curriculum, but by that time they suffered greatly from stasis and intellectual stagnation.

Galen describes his early life in on the affections of the mind. He was born in September AD 129.

His father, Aelius Nicon, was a wealthy patrician, an architect and builder, with eclectic interests including philosophy, mathematics, logic, astronomy, agriculture and literature.

Galen describes his father as a "highly amiable, just, good and benevolent man".

In 148, when he was 19, his father died, leaving him independently wealthy.

In 157, aged 28, he returned to Pergamon as physician to the gladiators of the High Priest of Asia, one of the most influential and wealthy men in Asia.

Galen was the physician to Commodus for much of the emperor’s life and treated his common illnesses.

He had experience with the epidemic, referring to it as very long lasting, and described its symptoms and his treatment of it.

Galen notes that the exanthema covered the victim’s entire body and was usually black.

Galen describes the symptoms of fever, vomiting, fetid breath, catarrh, cough, and ulceration of the larynx and trachea.

When the Peripatetic philosopher Eudemus became ill with quartan fever, Galen felt obliged to treat him "since he was my teacher and I happened to live nearby." Galen wrote: "I return to the case of Eudemus.

The 11th-century Suda lexicon states that Galen died at the age of 70, which would place his death in about the year 199.

Galen contributed a substantial amount to the Hippocratic understanding of pathology. Galen promoted this theory and the typology of human temperaments.

Galen’s principal interest was in human anatomy, but Roman law had prohibited the dissection of human cadavers since about 150 BC.

Among Galen’s major contributions to medicine was his work on the circulatory system. He was the first to recognize that there are distinct differences between venous (dark) and arterial (bright) blood.

In his work De motu musculorum, Galen explained the difference between motor and sensory nerves, discussed the concept of muscle tone, and explained the difference between agonists and antagonists.

Although the main focus of his work was on medicine, anatomy, and physiology, Galen also wrote about logic and philosophy.

Galen was well known for his advancements in the medical field and the circulatory system; he was also quite involved with philosophy. He developed his own tripartite soul following the examples of Plato.

One of Galen’s major works, On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, sought to demonstrate the unity of the two subjects and their views.

Galen believed there to be no distinction between the mental and the physical.

Another one of Galen's major works, On the Diagnosis and Cure of the Soul’s Passion, contained how to approach and treat psychological problems.

Galen may have produced more work than any author in antiquity, rivaling the quantity of work issued from Augustine of Hippo.

In his time, Galen's reputation as both physician and philosopher was legendary, the Emperor Marcus Aurelius describing him as "Primum sane medicorum esse, philosophorum autem solum" (first among doctors and unique among philosophers Praen 14: 660).

Galen's approach to medicine became and remains influential in the Islamic world. The first major translator of Galen into Arabic was the Syrian Christian Hunayn ibn Ishaq.

The influence of Galen's writings, including humorism, remains strong in modern Unani medicine, now closely identified with Islamic culture, and widely practiced from India (where it is officially recognized) to Morocco.

In the 1530s, the Flemish anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius took on a project to translate many of Galen's Greek texts into Latin.

Galenic scholarship remains an intense and vibrant field, following renewed interest in his work, dating from the German encyclopedia Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft.

Some Galenic teaching, such as his emphasis on bloodletting as a remedy for many ailments, however, remained influential until well into the 19th century.

Source: Link

1564 - 1616

1803 – 1882

1854 – 1900

1942 – 2016

1928 – 2014

1835 – 1910

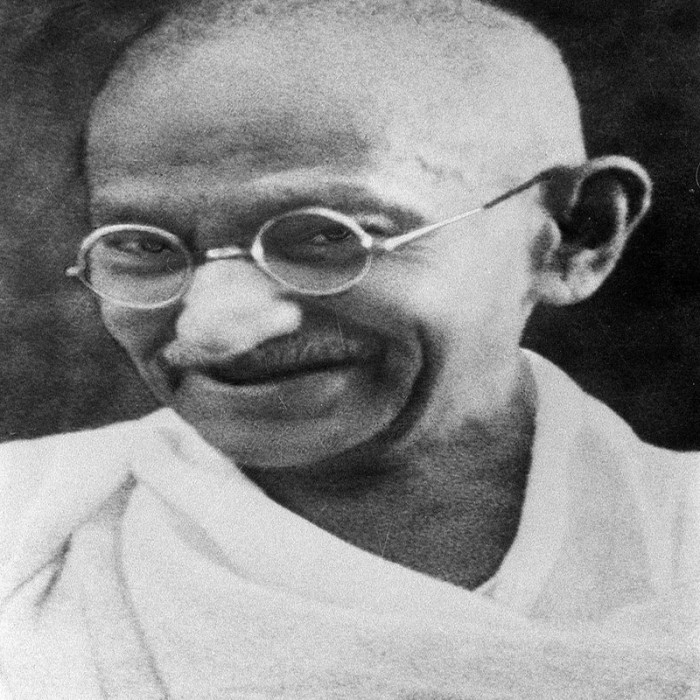

1869 – 1948

1884 – 1962

1898 – 1963

1929 – 1993

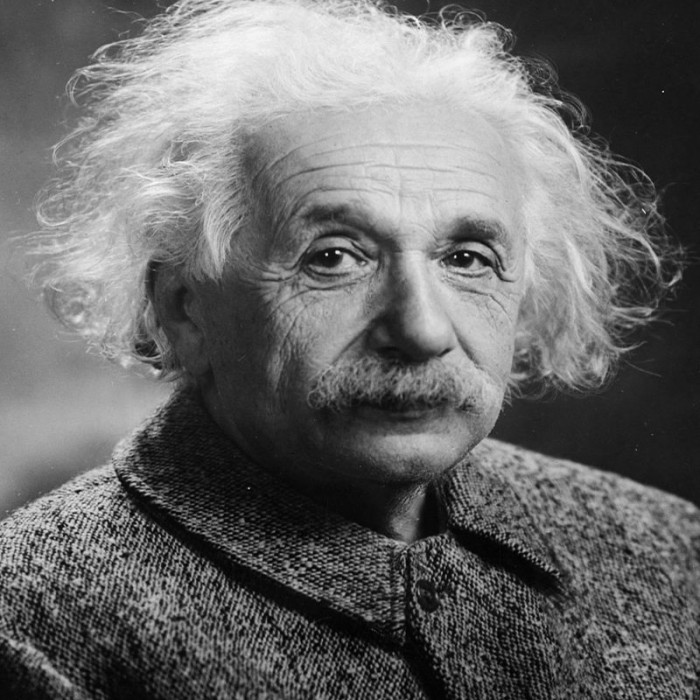

1879 – 1955

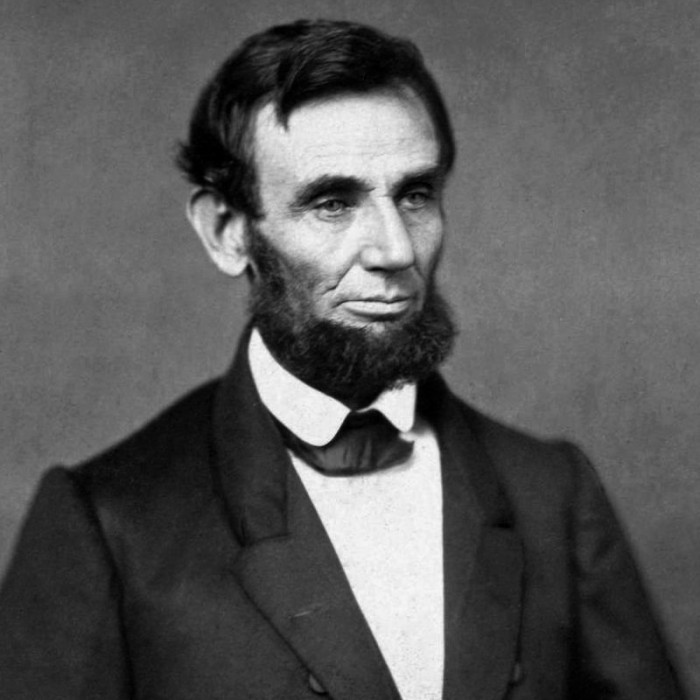

1809 – 1865

1807 – 1870

1800 – 1859

1795 – 1821

1755 – 1793

1984 -

1989 – 2011

1943 – 2001

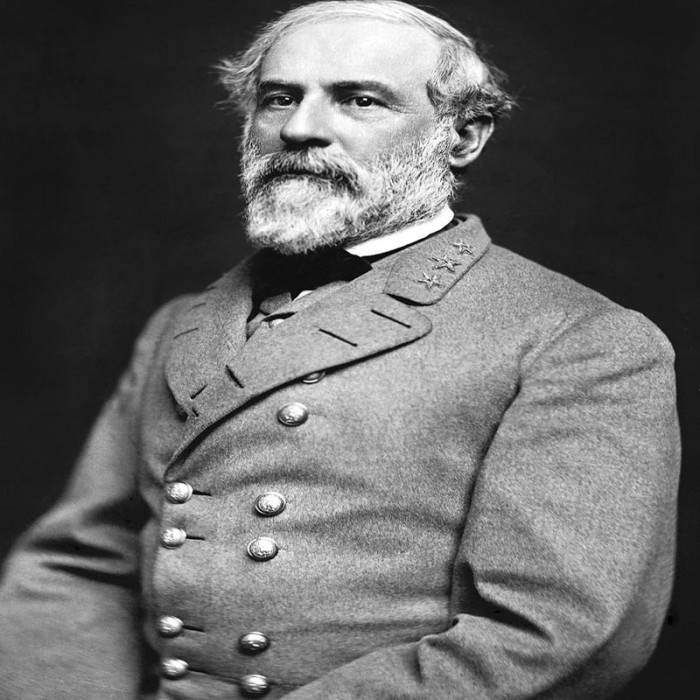

1815 – 1902

1929 – 1994

1767 – 1848