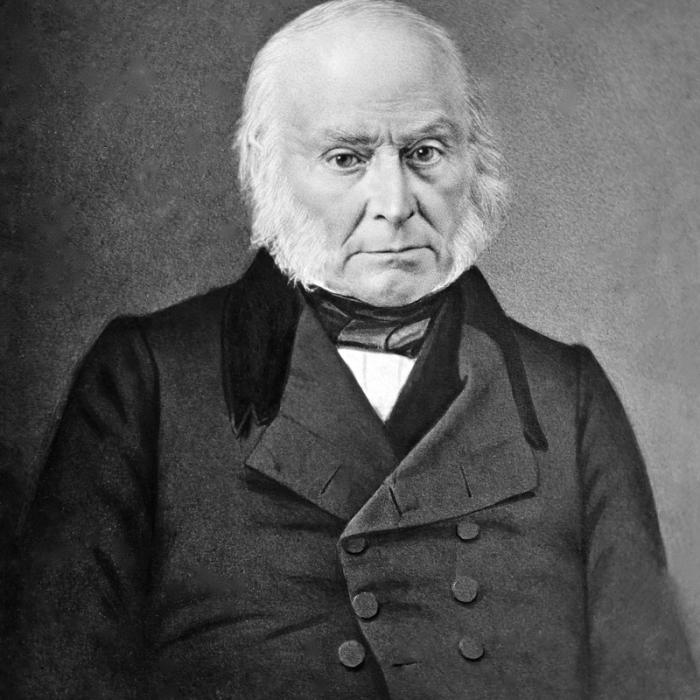

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "father of paleontology".

Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century and was instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in comparing living animals with fossils.

Cuvier's work is considered the foundation of vertebrate paleontology, and he expanded Linnaean taxonomy by grouping classes into phyla and incorporating both fossils and living species into the classification.

Cuvier is also known for establishing extinction as a fact—at the time, extinction was considered by many of Cuvier's contemporaries to be merely controversial speculation.

In his Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1813) Cuvier was interpreted to have proposed that new species were created after periodic catastrophic floods.

In this way, Cuvier became the most influential proponent of catastrophism in geology in the early 19th century.

His study of the strata of the Paris basin with Alexandre Brongniart established the basic principles of biostratigraphy.

Among his other accomplishments, Cuvier established that elephant-like bones found in the USA belonged to an extinct animal he later would name as a mastodon, and that a large skeleton dug up in Paraguay was of Megatherium, a giant, prehistoric ground sloth.

He named the pterosaur Pterodactylus, described the aquatic reptile Mosasaurus, and was one of the first people to suggest the earth had been dominated by reptiles, rather than mammals, in prehistoric times.

Cuvier is also remembered for strongly opposing theories of evolution, which at the time were mainly proposed by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

Cuvier believed there was no evidence for evolution, but rather evidence for cyclical creations and destructions of life forms by global extinction events such as deluges.

In 1830, Cuvier and Geoffroy engaged in a famous debate, which is said to exemplify the two major deviations in biological thinking at the time – whether animal structure was due to function or morphology.

His most famous work is Le Règne Animal (1817; English: The Animal Kingdom).

In 1819, he was created a peer for life in honor of his scientific contributions.

Thereafter, he was known as Baron Cuvier. He died in Paris during an epidemic of cholera.

Some of Cuvier's most influential followers were Louis Agassiz on the continent and in the United States, and Richard Owen in Britain.

His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, France (in department of Doubs), where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation.

During his gymnasium years, he had little trouble acquiring Latin and Greek, and was always at the head of his class in mathematics, history, and geography.

At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's Historiae Animalium, the work that first sparked his interest in natural history.

Cuvier spent an additional four years at the Caroline Academy in Stuttgart, where he excelled in all of his coursework.

So in July 1788, he took a job at Fiquainville chateau in Normandy as tutor to the only son of the Comte d'Héricy, a Protestant noble.

Cuvier regularly attended meetings held at the nearby town of Valmont for the discussion of agricultural topics.

The Institut de France was founded in the same year, and he was elected a member of its Academy of Sciences.

On 4 April 1796 he began to lecture at the École Centrale du Pantheon and, at the opening of the National Institute in April, he read his first paleontological paper, which subsequently was published in 1800.

In this paper, he analyzed skeletal remains of Indian and African elephants, as well as mammoth fossils, and a fossil skeleton known at that time as the 'Ohio animal'.

Cuvier's analysis established, for the first time, the fact that African and Indian elephants were different species and that mammoths were not the same species as either African or Indian elephants, so must be extinct.

Years later, in 1806, he would return to the 'Ohio animal' in another paper and give it the name, "mastodon".

In his second paper in 1796, he described and analyzed a large skeleton found in Paraguay, which he would name Megatherium.

Together, these two 1796 papers were a seminal or landmark event, becoming a turning point in the history of paleontology, and in the development of comparative anatomy, as well.

In 1799, he succeeded Daubenton as professor of natural history in the Collège de France. In 1802, he became titular professor at the Jardin des Plantes.

In 1806, he became a foreign member of the Royal Society, and in 1812, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1812 he became a correspondent for the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, and became member in 1827.

Cuvier was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822.

In 1812, Cuvier made what the cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans called his "Rash dictum": he remarked that it was unlikely that any large animal remained undiscovered.

Cuvier was by birth, education, and conviction a devout Lutheran, and remained Protestant throughout his life while regularly attending church services.

From 1822 until his death in 1832, Cuvier was Grand Master of the Protestant Faculties of Theology of the French University.

Cuvier was critical of theories of evolution, including those proposed by his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, which involved the gradual transmutation of one form into another.

He also observed that Napoleon's expedition to Egypt had retrieved animals mummified thousands of years previously that seemed no different from their modern counterparts.

In 1795, Georges Cuvier did some of his anatomical studies on animals at the National Museum in Paris.

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct.

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct.

In a 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in some plaster quarries near Paris, Cuvier states what is known as the principle of the correlation of parts.

At the Paris Museum, Cuvier furthered his studies on the anatomical classification of animals.

In his anatomical studies, Cuvier believed function played a bigger role than form in the field of taxonomy.

In 1798 Cuvier published his first independent work, the Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux.

In 1800 he published the Leçons d'anatomie comparée, assisted by A. M. C. Duméril for the first two volumes and Georges Louis Duvernoy for the three later ones.

Cuvier's researches on fish, begun in 1801, finally culminated in the publication of the Histoire naturelle des poisons. Cuvier's work on this project extended over the years 1828–1831.

Cuvier was a Protestant and a believer in monogenism, who held that all men descended from the biblical Adam, although his position usually was confused as polygenist.

In Cuvier’s published reports, he compared her with the orangutan and the said she was among the lowest of the human species.

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and paleontology Cuvier carried out a vast amount of work as perpetual secretary of the National Institute.

In 1826 he was made grand officer of the Legion of Honour; he subsequently was appointed president of the council of state.

He served as a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres from 1830 to his death.

A member of the Doctrinaires, he was nominated to the ministry of the interior in the beginning of 1832.

Cuvier Island in New Zealand was named after Cuvier by D'Urville.

There also are some extinct animals named after Cuvier, such as the South American giant sloth Catonyx cuvieri.

Source: Link

1564 - 1616

1803 – 1882

1854 – 1900

1942 – 2016

1928 – 2014

1835 – 1910

1869 – 1948

1884 – 1962

1898 – 1963

1929 – 1993

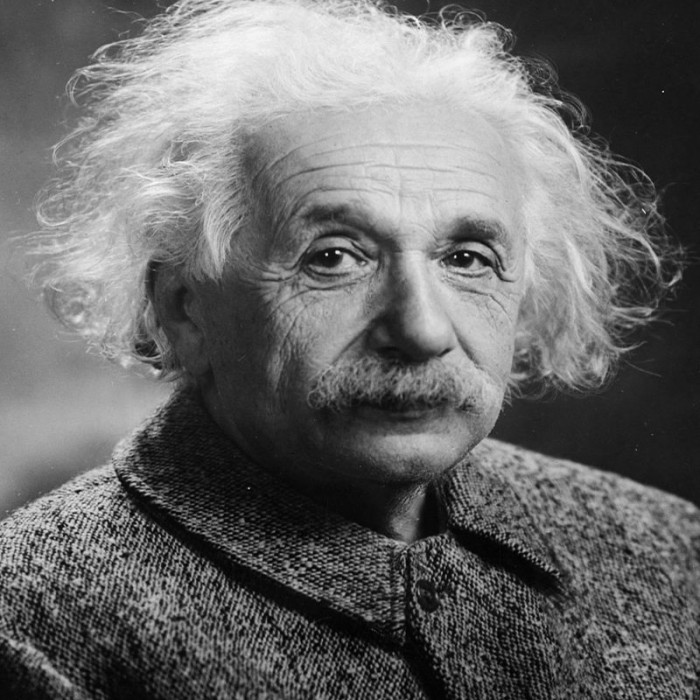

1879 – 1955

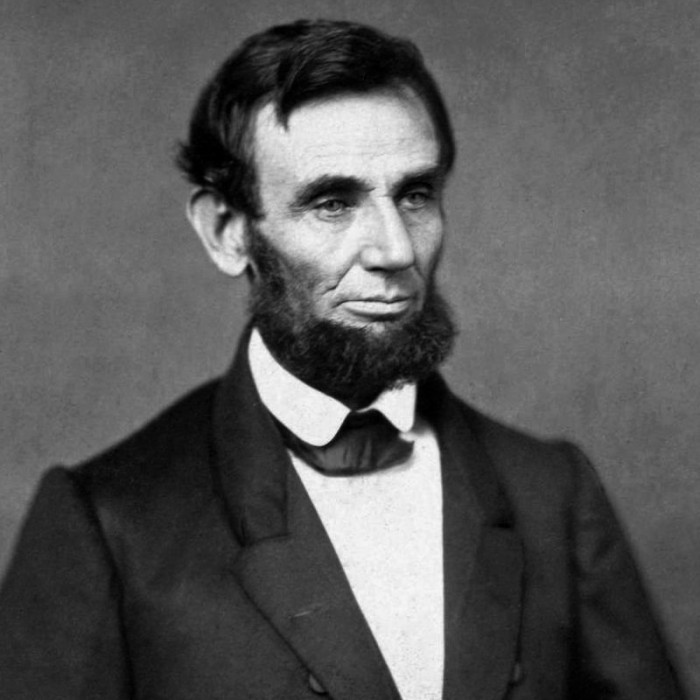

1809 – 1865

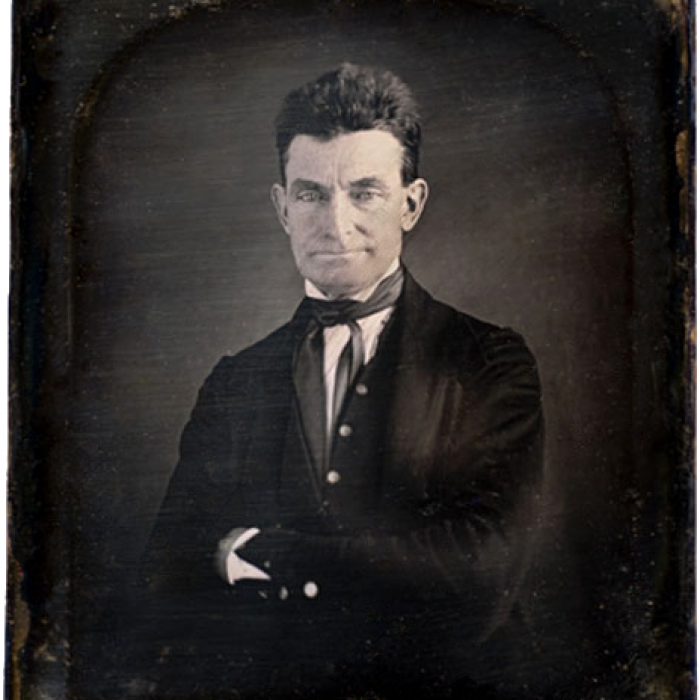

1807 – 1870

1800 – 1859

1795 – 1821

1755 – 1793

1984 -

1989 – 2011

1943 – 2001

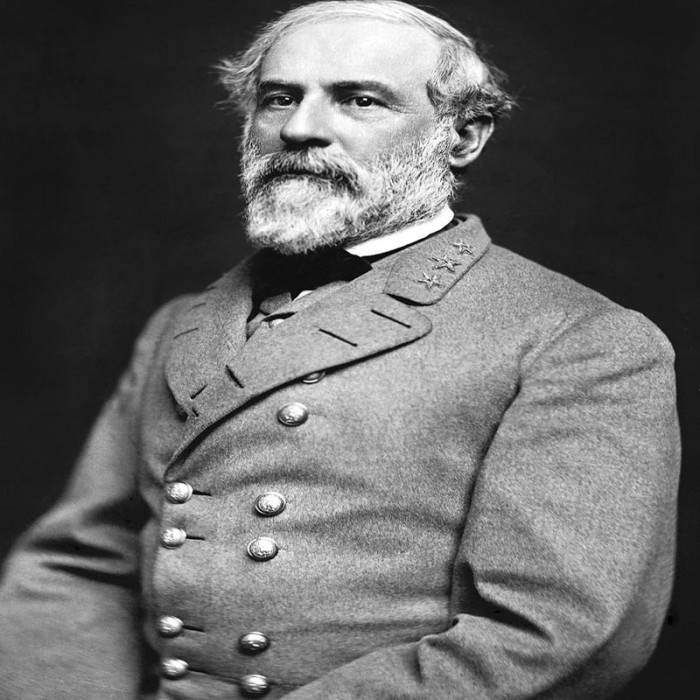

1815 – 1902

1929 – 1994

1767 – 1848