Ernst Walter Mayr (5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists.

He was also a renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, philosopher of biology, and historian of science.

His work contributed to the conceptual revolution that led to the modern evolutionary synthesis of Mendelian genetics, systematics, and Darwinian evolution, and to the development of the biological species concept.

Ernst Mayr approached the problem with a new definition for species.

In his book Systematics and the Origin of Species (1942) he wrote that a species is not just a group of morphologically similar individuals, but a group that can breed only among themselves, excluding all others.

His theory of peripatric speciation, based on his work on birds, is still considered a leading mode of speciation, and was the theoretical underpinning for the theory of punctuated equilibrium, proposed by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould.

Mayr is sometimes credited with inventing modern philosophy of biology, particularly the part related to evolutionary biology, which he distinguished from physics due to its introduction of (natural) history into science.

Mayr was the second son of Helene Pusinelli and Dr. Otto Mayr. His father was a jurist but took an interest in natural history and took the children out on field trips.

He learnt all the local birds in Würzburg from his elder brother Otto. He also had access to a natural history magazine for amateurs, Kosmos.

In April 1922, while still in high school, he joined the newly founded Saxony Ornithologists’ Association. Here he met Rudolf Zimmermann, who became his ornithological mentor.

In February 1923, Mayr passed his high school examination (Abitur) and his mother rewarded him with a pair of binoculars.

On 23 March 1923 on the lakes of Moritzburg, the Frauenteich, he spotted what he identified as a red-crested pochard.

Mayr could work as a volunteer in the ornithological section of the museum. Mayr wrote about this event, "It was as if someone had given me the key to heaven."

He entered the University of Greifswald in 1923 and, according to Mayr himself, "took the medical curriculum but after only a year, he decided to leave medicine and enrolled at the Faculty of Biological Sciences."

Mayr was endlessly interested in ornithology and "chose Greifswald at the Baltic for my studies for no other reason than that ... it was situated in the ornithologically most interesting area."

Mayr completed his doctorate in ornithology at the University of Berlin under Dr. Carl Zimmer, who was a full professor (Ordentlicher Professor), on 24 June 1926 at the age of 21.

On 1 July he accepted the position offered to him at the museum for a monthly salary of 330.54 Reichsmark.

In New Guinea, Mayr collected several thousand bird skins (he named 26 new bird species during his lifetime) and, in the process also named 38 new orchid species.

He returned to Germany in 1930, and in 1931 he accepted a curatorial position at the American Museum of Natural History, where he played the important role of brokering and acquiring the Walter Rothschild collection of bird skins, which was being sold in order to pay off a blackmailer.

During his time at the museum he produced numerous publications on bird taxonomy, and in 1942 his first book Systematics and the Origin of Species, which completed the evolutionary synthesis started by Darwin.

After Mayr was appointed at the American Museum of Natural History, he influenced American ornithological research by mentoring young birdwatchers.

Mayr was surprised at the differences between American and German birding societies.

He noted that the German society was "far more scientific, far more interested in life histories and breeding bird species, as well as in reports on recent literature."

Mayr also greatly influenced the American ornithologist Margaret Morse Nice. Mayr encouraged her to correspond with European ornithologists and helped her in her landmark study on song sparrows.

Mayr joined the faculty of Harvard University in 1953, where he also served as director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology from 1961 to 1970.

He retired in 1975 as emeritus professor of zoology, showered with honors.

Following his retirement, he went on to publish more than 200 articles, in a variety of journals—more than some reputable scientists publish in their entire careers; 14 of his 25 books were published after he was 65.

On his 100th birthday, he was interviewed by Scientific American magazine.

Mayr died on 3 February 2005 in his retirement home in Bedford, Massachusetts after a short illness.

The awards that Mayr received include the National Medal of Science, the Balzan Prize, the Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society, the International Prize for Biology and many others.

In 1939 he was elected a Corresponding Member of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union. He was awarded the 1946 Leidy Award from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Mayr was co-author of six global reviews of bird species new to science.

Mayr said he was an atheist towards "the idea of a personal God" because "there is nothing that supports [it]"

As a traditionally trained biologist, Mayr was often highly critical of early mathematical approaches to evolution such as those of J.B.S. Haldane, famously calling such approaches "beanbag genetics" in 1959.

Mayr was an outspoken defender of the scientific method, and one known to sharply critique science on the edge.

Mayr rejected the idea of a gene-centered view of evolution and starkly but politely criticized Richard Dawkins' ideas.

Mayr insisted that the entire genome should be considered as the target of selection, rather than individual genes.

Source: Link

1564 - 1616

1803 – 1882

1854 – 1900

1942 – 2016

1928 – 2014

1835 – 1910

1869 – 1948

1884 – 1962

1898 – 1963

1929 – 1993

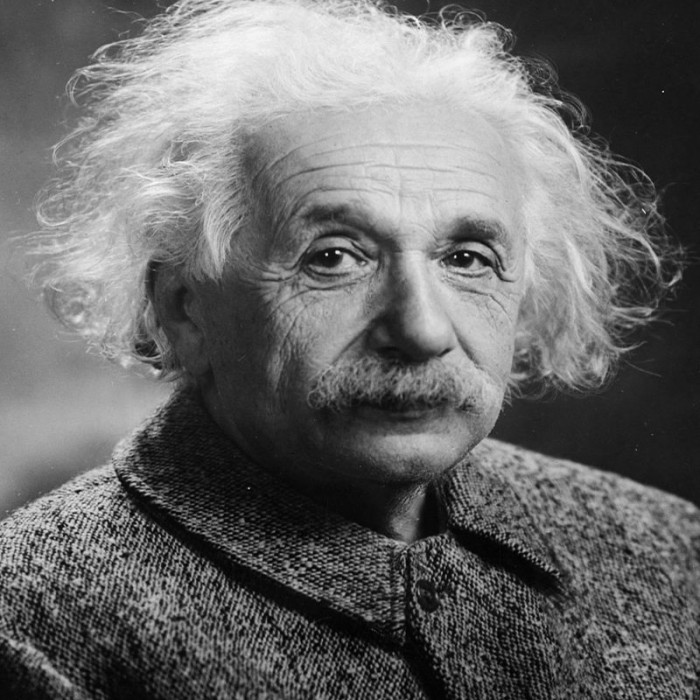

1879 – 1955

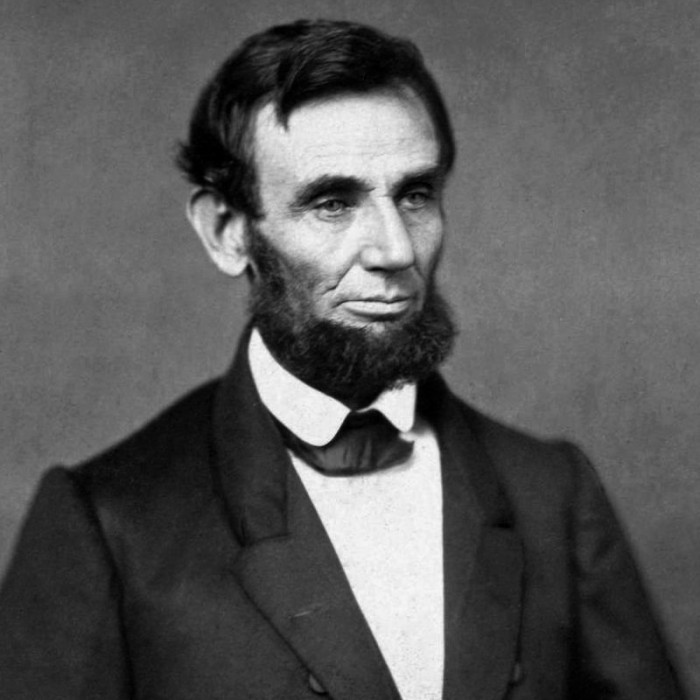

1809 – 1865

1807 – 1870

1800 – 1859

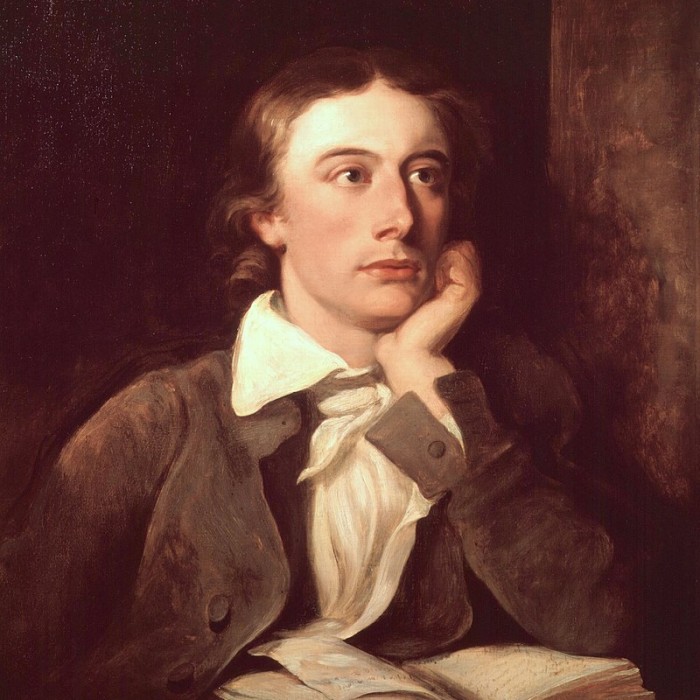

1795 – 1821

1755 – 1793

1984 -

1989 – 2011

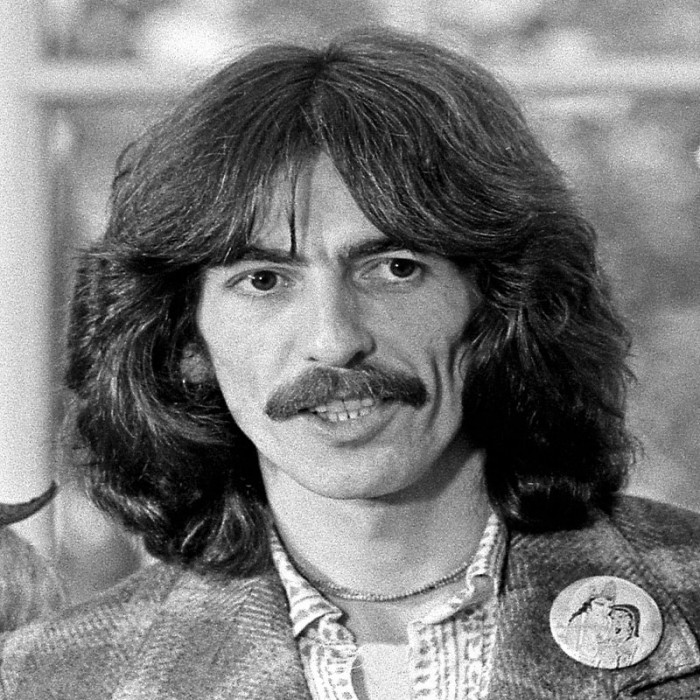

1943 – 2001

1815 – 1902

1929 – 1994

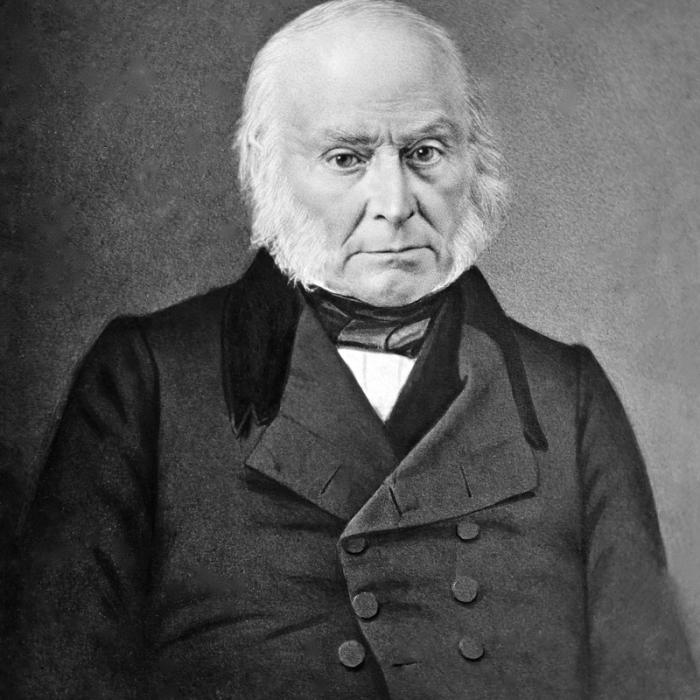

1767 – 1848