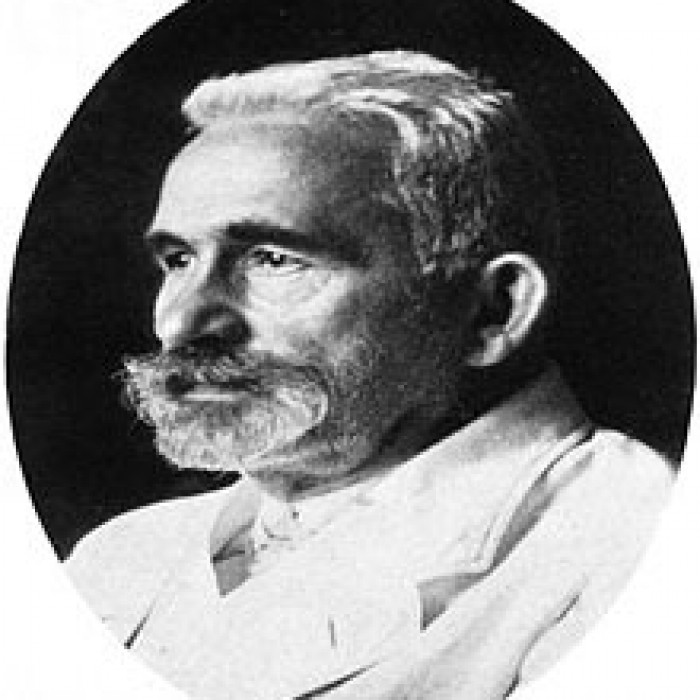

Emil Kraepelin (15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926) was a German psychiatrist.

H. J. Eysenck's Encyclopedia of Psychology identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psychiatric genetics.

Kraepelin was a strong and influential proponent of eugenics and racial hygiene, and believed the chief origin of psychiatric disease to be biological and genetic malfunction.

His theories dominated psychiatry at the start of the 20th century and, despite the later psychodynamic influence of Sigmund Freud and his disciples, enjoyed a revival at century's end.

While he proclaimed his own high clinical standards of gathering information "by means of expert analysis of individual cases", he also drew on reported observations of officials not trained in psychiatry.

His textbooks do not contain detailed case histories of individuals but mosaiclike compilations of typical statements and behaviors from patients with a specific diagnosis.

He has been described as a "scientific manager" and political operator, who developed a large-scale, clinically oriented, epidemiological research programme.

Kraepelin, whose father, Karl Wilhelm, was a former opera singer, music teacher, and later successful story teller, was born in 1856 in Neustrelitz, in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in Germany.

He was first introduced to biology by his brother Karl, 10 years older and, later, the director of the Zoological Museum of Hamburg.

Kraepelin began his medical studies in 1874 at the University of Leipzig and completed them at the University of Würzburg (1877–78).

At Leipzig, he studied neuropathology under Paul Flechsig and experimental psychology with Wilhelm Wundt.

Kraepelin would be a disciple of Wundt and had a lifelong interest in experimental psychology based on his theories.

Returning to the University of Leipzig in February 1882, he worked in Wilhelm Heinrich Erb's neurology clinic and in Wundt's psychopharmacology laboratory.

He completed his Habilitation thesis at Leipzig; it was entitled "The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry".

In 1884 he became senior physician in the Prussian provincial town of Leubus, Silesia Province, and the following year he was appointed director of the Treatment and Nursing Institute in Dresden.

On 1 July 1886, at the age of 30, Kraepelin was named Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (today the University of Tartu) in what is today Estonia (see Burgmair et al., vol. IV).

On 5 December 1890, he became department head at the University of Heidelberg, where he remained until 1904. While at Dorpat he became the director of the 80-bed University Clinic.

In 1903 Kraepelin moved to Munich to become Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at the University of Munich.

He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1908.

In 1912 at the request of the German Society of Psychiatry, he began plans to establish a centre for research.

In the later period of his career, as a convinced champion of social Darwinism, he actively promoted a policy and research agenda in racial hygiene and eugenics.

Kraepelin retired from teaching at the age of 66, spending his remaining years establishing the Institute.

The ninth and final edition of his Textbook was published in 1927, shortly after his death. It comprised four volumes and was ten times larger than the first edition of 1883.

In the last years of his life he Kraepelin was preoccupied with Buddhist teachings and was planning to visit Buddhist shrines at the time of his death, according to his daughter, Antonie Schmidt-Kraepelin.

Kraepelin announced that he had found a new way of looking at mental illness, referring to the traditional view as "symptomatic" and to his view as "clinical".

Kraepelin is specifically credited with the classification of what was previously considered to be a unitary concept of psychosis, into two distinct forms (known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy).

Kraepelin also demonstrated specific patterns in the genetics of these disorders and specific and characteristic patterns in their course and outcome.

In the first through sixth edition of Kraepelin's influential psychiatry textbook, there was a section on moral insanity, which meant then a disorder of the emotions or moral sense without apparent delusions or hallucinations.

In fact from 1904 Kraepelin changed the section heading to "The born criminal", moving it from under "Congenital feeble-mindedness" to a new chapter on "Psychopathic personalities". They were treated under a theory of degeneration.

Kraepelin had referred to psychopathic conditions (or "states") in his 1896 edition, including compulsive insanity, impulsive insanity, homosexuality, and mood disturbances.

Kraepelin postulated that there is a specific brain or other biological pathology underlying each of the major psychiatric disorders. As a colleague of Alois Alzheimer, he was a co-discoverer of Alzheimer's disease, and his laboratory discovered its pathological basis.

Kraepelin's great contribution in classifying schizophrenia and manic depression remains relatively unknown to the general public, and his work, which had neither the literary quality nor paradigmatic power of Freud's, is little read outside scholarly circles.

Kraepelin has been described as a "scientific manager" and political operator, who developed a large-scale, clinically oriented, epidemiological research programme.

Kraepelin, on the basis on the dream-psychosis analogy, studied for more than 20 years language disorder in dreams in order to study indirectly schizophasia.

One of his own famous contributions to this journal also appeared in the form of a monograph (105 pp.) entitled Über Sprachstörungen im Traume (On Language Disturbances in Dreams).

Source: Link

1564 - 1616

1803 – 1882

1854 – 1900

1942 – 2016

1928 – 2014

1835 – 1910

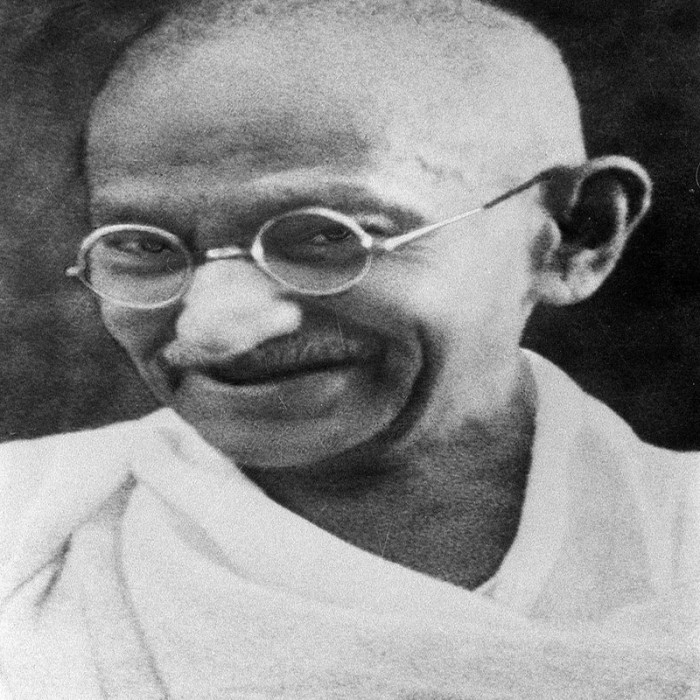

1869 – 1948

1884 – 1962

1898 – 1963

1929 – 1993

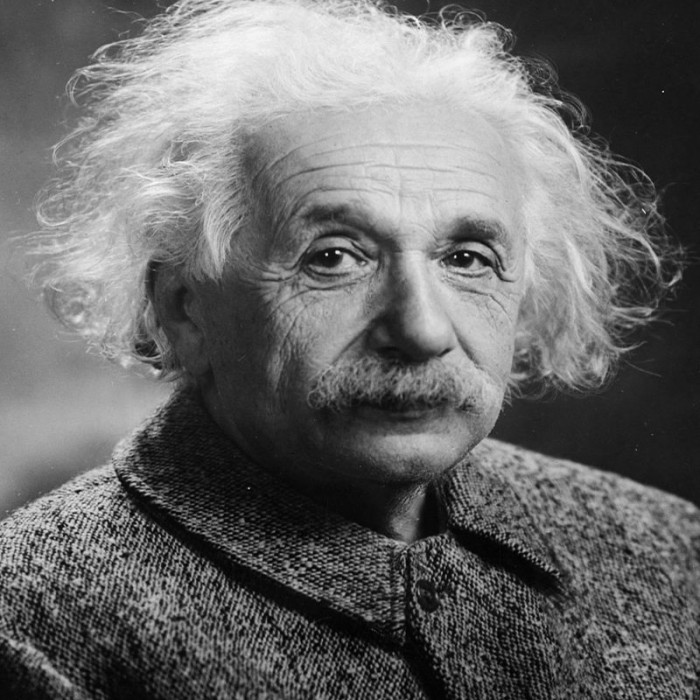

1879 – 1955

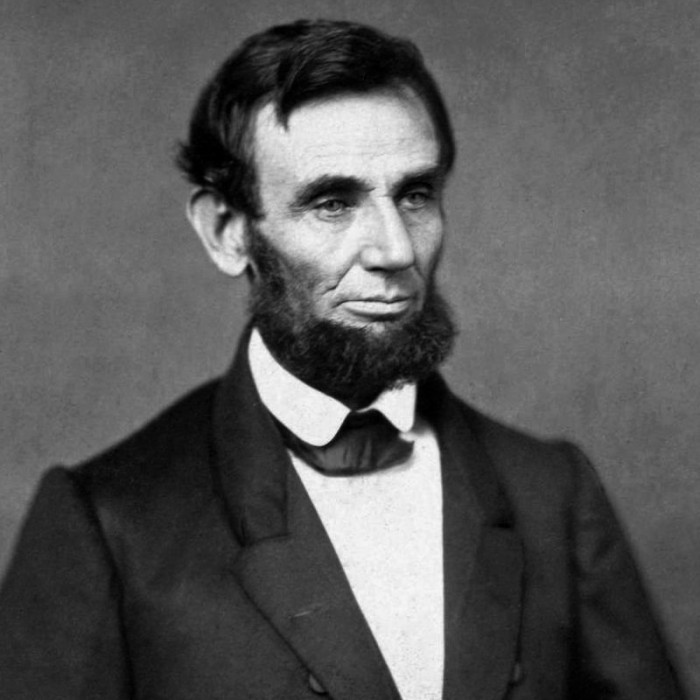

1809 – 1865

1807 – 1870

1800 – 1859

1795 – 1821

1755 – 1793

1984 -

1989 – 2011

1943 – 2001

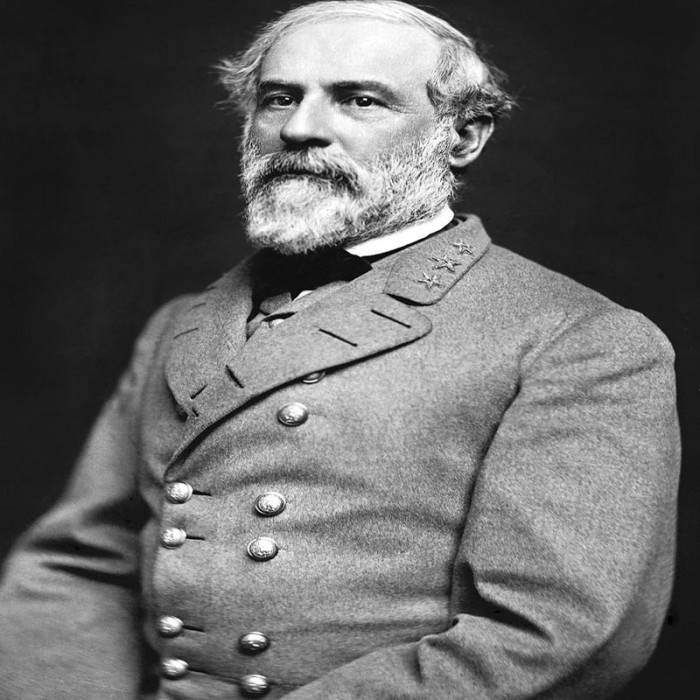

1815 – 1902

1929 – 1994

1767 – 1848