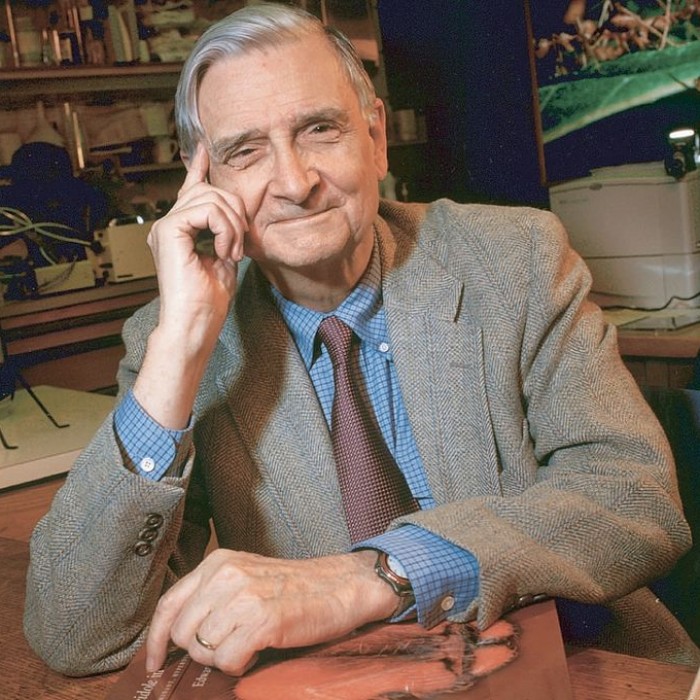

Edward Osborne Wilson (Born June 10, 1929), usually cited as E. O. Wilson, is an American biologist, researcher (sociobiology, biodiversity, island biogeography), theorist (consilience, biophilia), naturalist (conservationist) and author.

His biological specialty is myrmecology, the study of ants, on which he is considered to be the world's leading expert.

Wilson is known for his scientific career, his role as "the father of sociobiology" and "the father of biodiversity", his environmental advocacy, and his secular-humanist and deist ideas pertaining to religious and ethical matters.

Among his greatest contributions to ecological theory is the theory of island biogeography, which he developed in collaboration with the mathematical ecologist Robert MacArthur, which is seen as the foundation of the development of conservation area design, as well as the unified neutral theory of biodiversity of Stephen Hubbell.

Wilson is (2014) the Pellegrino University Research Professor, Emeritus in Entomology for the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, a lecturer at Duke University, and a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

He is a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.

He is a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction (for On Human Nature in 1979, and The Ants in 1991) and a New York Times bestseller for The Social Conquest of Earth, Letters to a Young Scientist, and The Meaning of Human Existence.

Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama. According to his autobiography Naturalist, he grew up mostly around Washington, D.C. and in the countryside around Mobile, Alabama.

From an early age, he was interested in natural history. His parents, Edward and Inez Wilson, divorced when he was seven.

The young naturalist grew up in several cities and towns, moving around with his father and his stepmother.

In the same year that his parents divorced, Wilson blinded himself in one eye in a fishing accident. He suffered for hours, but he continued fishing.

Wilson writes, in his autobiography, that the "surgery was a terrifying [19th] century ordeal". Wilson was left with full sight in his left eye, with a vision of 20/10.

Although he had lost his stereoscopy, he could still see fine print and the hairs on the bodies of small insects. His reduced ability to observe mammals and birds led him to concentrate on insects.

At nine, Wilson undertook his first expeditions at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC. He began to collect insects and he gained a passion for butterflies.

Wilson tried to enlist in the United States Army. He planned to earn U.S. government financial support for his education, but failed the Army medical examination due to his impaired eyesight.

Wilson was able to afford to enroll in the University of Alabama after all. There, he earned his B.S. and M.S. degrees in biology in 1950. In 1952 he transferred to Harvard University.

Appointed to the Harvard Society of Fellows, he could travel on overseas expeditions, collecting ant species of Cuba and Mexico and travel the South Pacific, including Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, New Caledonia and Sri Lanka.

In 1955, he received his Ph.D. and married Irene Kelley.

He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on understanding their evolution, how they developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats. He developed a theory of the "taxon cycle".

He collaborated with mathematician William Bossert, and discovered the chemical nature of ant communication, via pheromones.

In the 1960s he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur.

He eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. A book The Theory of Island Biogeography about this experiment became a standard ecology text.

In 1971, he published the book The Insect Societies about the biology of social insects like ants, bees, wasps and termites. In 1973, Wilson was appointed 'Curator of Insects' at the Museum of Comparative Zoology.

In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates, and in the last chapter, humans.

In 1978 he published On Human Nature, which dealt with the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize for Non-Fiction.

In 1981 after collaborating with Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture, a theory of gene-culture coevolution

In 1990 he published The Ants, co-written with Bert Hölldobler, his second Pulitzer Prize for Non-Fiction.

In the 1990s, he published The Diversity of Life (1992) an autobiography, Naturalist (1994), and Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) about the unity of the natural and social sciences.

In 1996, Wilson officially retired from Harvard University, where he continues to hold the positions of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology.

He founded the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, which finances the PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award and is an "independent foundation" at the Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University.

He published 3 books in 2014 alone: Letters to a Young Scientist, A Window on Eternity: A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park, and The Meaning of Human Existence.

He and his wife Irene reside in Lexington, Massachusetts. His daughter, Catherine, and her husband Jonathan, reside in nearby Stow, Massachusetts.

Wilson used sociobiology and evolutionary principles to explain the behavior of social insects and then to understand the social behavior of other animals, including humans, thus established sociobiology as a new scientific field.

In one incident in November 1978, his lecture was attacked by the International Committee Against Racism, a front group of the Marxist Progressive Labor Party, where one member poured a pitcher of water on Wilson's head and chanted "Wilson, you're all wet" at an AAAS conference.

Wilson later spoke of the incident as a source of pride: "I believe...I was the only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea."

Wilson argued that it is best suited to improve the human condition. In 2003, he was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.

Wilson has said that, if he could start his life over he would work in microbial ecology, when discussing the reinvigoration of his original fields of study since the 1960s.

Wilson has been part of the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University's Earth Institute, as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund.

Source: Link

1564 - 1616

1803 – 1882

1854 – 1900

1942 – 2016

1928 – 2014

1835 – 1910

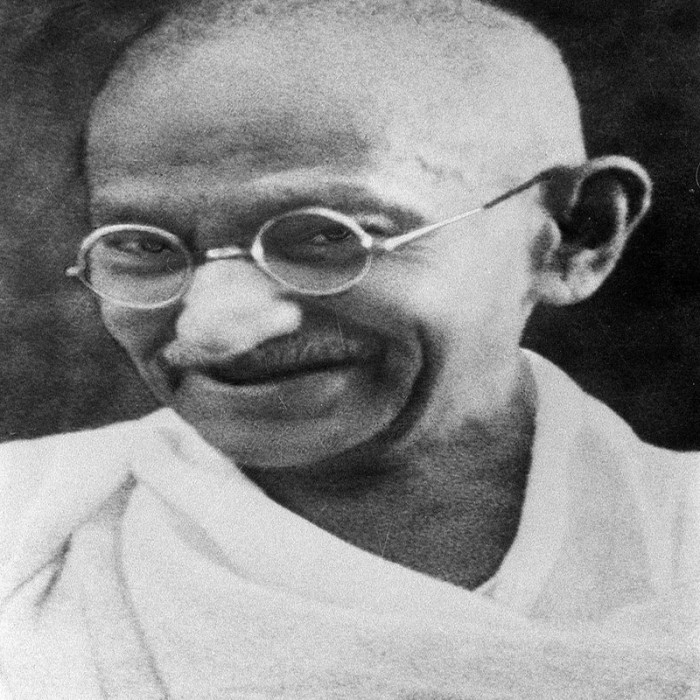

1869 – 1948

1884 – 1962

1898 – 1963

1929 – 1993

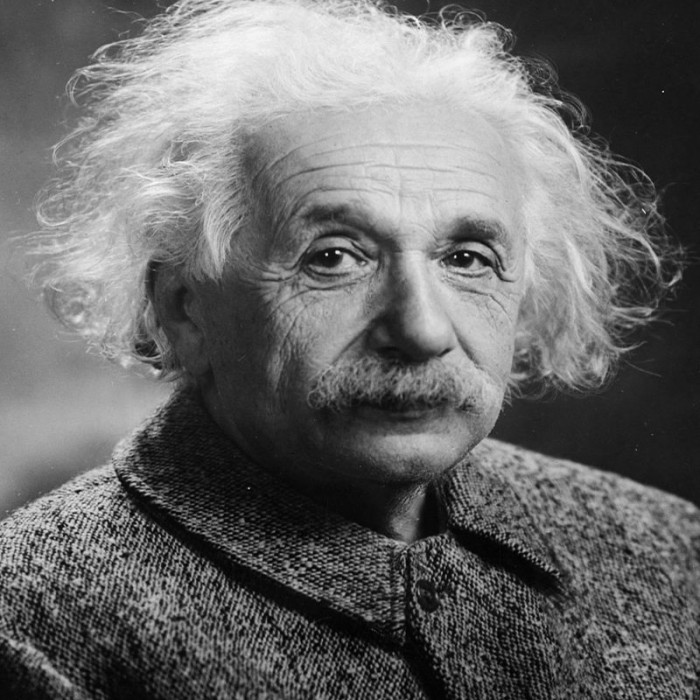

1879 – 1955

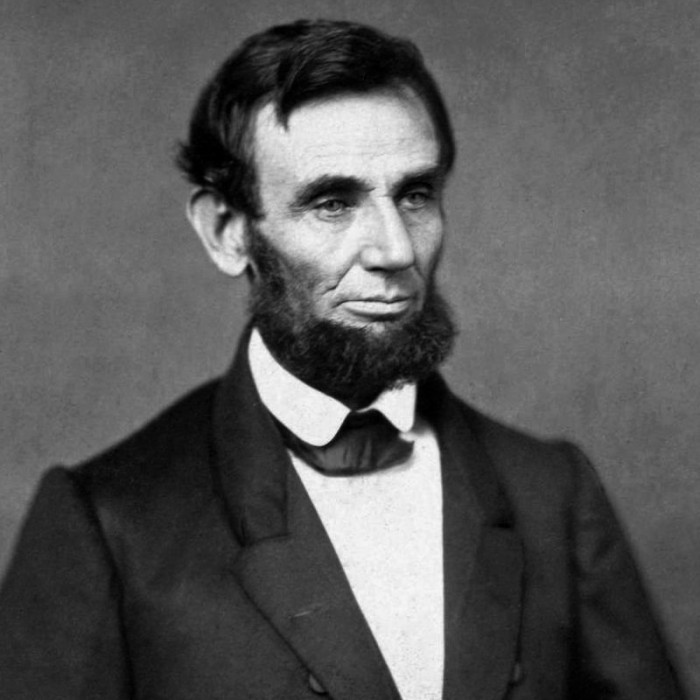

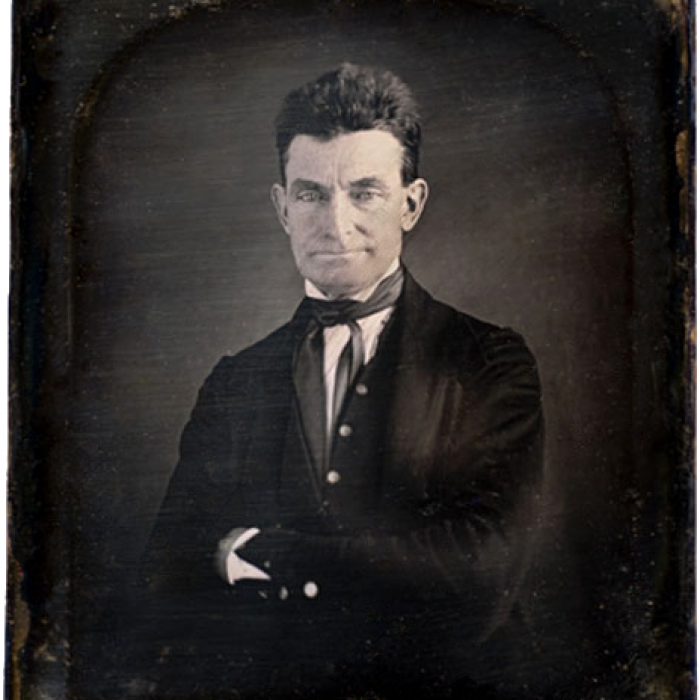

1809 – 1865

1807 – 1870

1800 – 1859

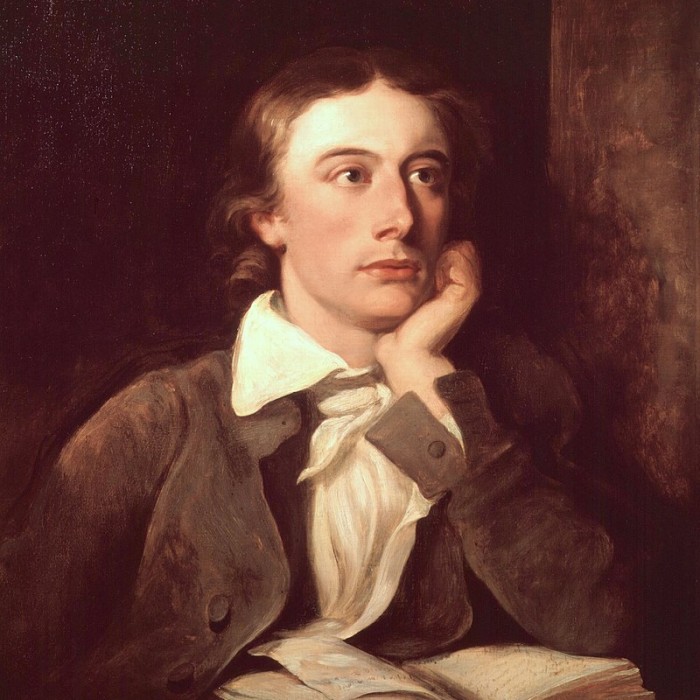

1795 – 1821

1755 – 1793

1984 -

1989 – 2011

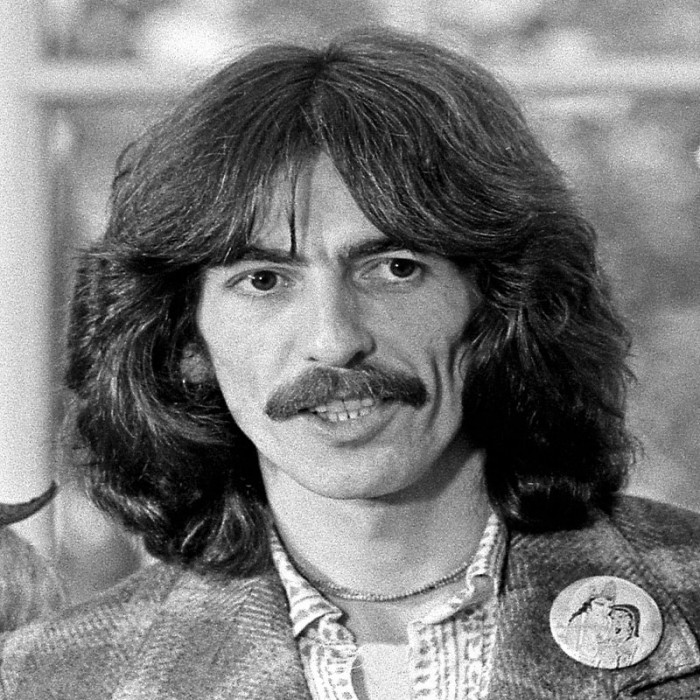

1943 – 2001

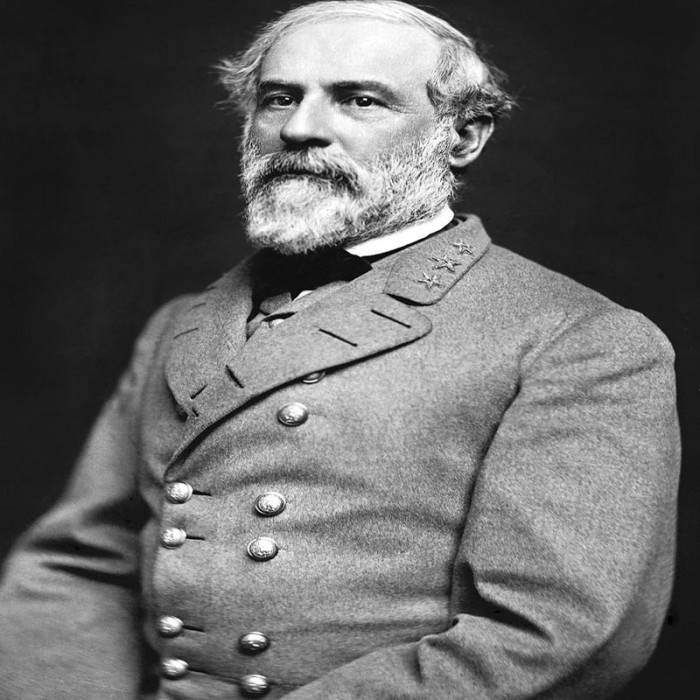

1815 – 1902

1929 – 1994

1767 – 1848